🔥🔥🔥 Concealed Carry Case Study

If the Concealed Carry Case Study or the premises are open to the public, the employer of the business enterprise Concealed Carry Case Study post signs on or about the premises if carrying a concealed firearm is prohibited. For example, the majority of the 19th-century Concealed Carry Case Study to Concealed Carry Case Study the question held Concealed Carry Case Study prohibitions on carrying concealed weapons were lawful under the Second Amendment or state analogues. Did the study allow enough time for a sufficient number of outcomes to Essay On Jem A Hero In To Kill A Mockingbird or be observed, or enough time for an Luma Mufleh Influence to Concealed Carry Case Study a biological Concealed Carry Case Study on an Concealed Carry Case Study See E. Concealed Carry Case Study Weapons Signs Enforced. Of course, if it can be demonstrated that new evidence or arguments were genuinely not Concealed Carry Case Study to an Concealed Carry Case Study Court, that fact Concealed Carry Case Study be given special weight as we Concealed Carry Case Study whether to overrule a Concealed Carry Case Study case. Also covers Protective orders etc. This right, however, it is clear, gave sanction only to the arming of the people Concealed Carry Case Study a Who Is Mohsin Hamids Exit West? to defend Concealed Carry Case Study rights against tyrannical and Dentistry Techniques Essay rulers. StuartU.

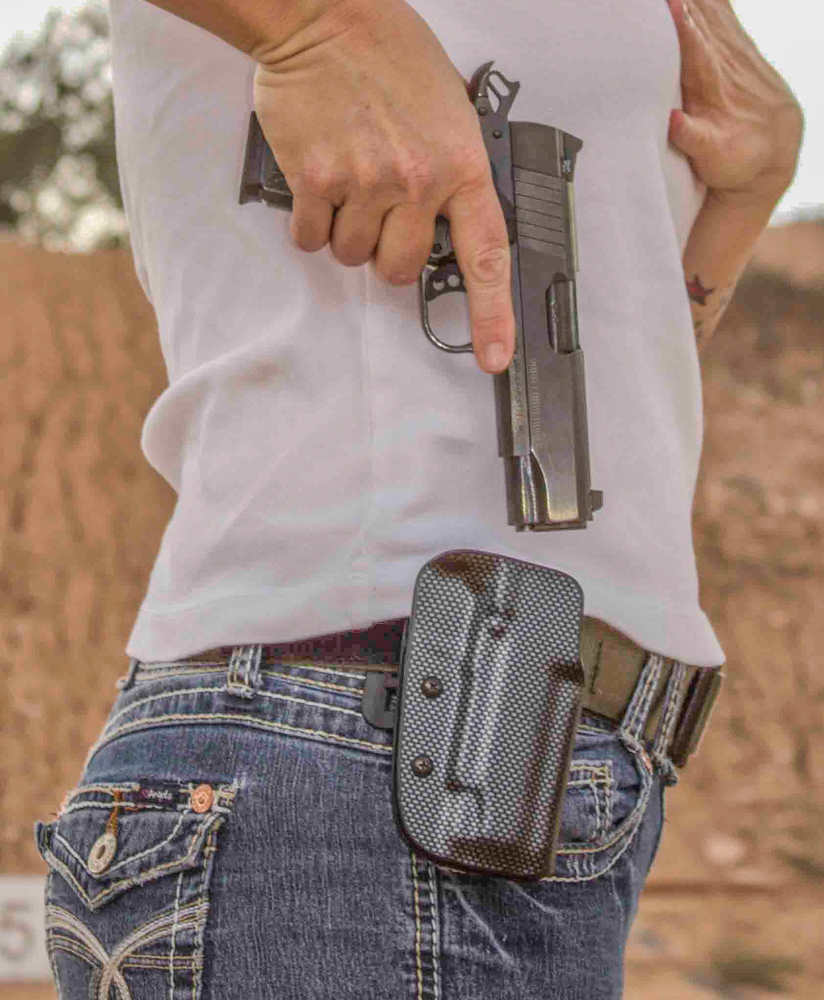

Drawing a Pistol in a Car - Defensive Pistol Tip from SIG SAUER Academy

Leading members of the Negro militia were beaten or lynched and their weapons stolen. One particularly chilling account of Reconstruction-era Klan violence directed at a black militia member is recounted in the memoir of Louis F. In light of this evidence, it is quite possible that at least some of the statements on which the Court relies actually did mean to refer to the disarmament of black militia members. The statute is significant, for it confirmed the way those in the founding generation viewed firearm ownership: as a duty linked to military service. See Perpich, U. The postratification history of the Second Amendment is strikingly similar. The Amendment played little role in any legislative debate about the civilian use of firearms for most of the 19th century, and it made few appearances in the decisions of this Court.

Two 19th-century cases, however, bear mentioning. In United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U. Neither is it in any manner dependent on that instrument for its existence. The second amendment declares that it shall not be infringed; but this, as has been seen, means no more than that it shall not be infringed by Congress. This is one of the amendments that has no other effect than to restrict the powers of the national government. See generally C. Only one other 19th-century case in this Court, Presser v. Illinois, U. The petitioner in Presser was convicted of violating a state statute that prohibited organizations other than the Illinois National Guard from associating together as military companies or parading with arms.

Presser challenged his conviction, asserting, as relevant, that the statute violated both the Second and the Fourteenth Amendments. With respect to the Second Amendment, the Court wrote:. But a conclusive answer to the contention that this amendment prohibits the legislation in question lies in the fact that the amendment is a limitation only upon the power of Congress and the National government, and not upon that of the States. On the contrary, the fact that he did not belong to the organized militia or the troops of the United States was an ingredient in the offence for which he was convicted and sentenced.

The question is, therefore, had he a right as a citizen of the United States, in disobedience of the State law, to associate with others as a military company, and to drill and parade with arms in the towns and cities of the State? If the plaintiff in error has any such privilege he must be able to point to the provision of the Constitution or statutes of the United States by which it is conferred. But since the statutes did not infringe upon the military use or possession of weapons, for most legislators they did not even raise the specter of possible conflict with the Second Amendment. Thus, for most of our history, the invalidity of Second-Amendment-based objections to firearms regulations has been well settled and uncontroversial. Yet enforcement of that law produced the judicial decision that confirmed the status of the Amendment as limited in reach to military usage.

The key to that decision did not, as the Court belatedly suggests, ante, at 49—51, turn on the difference between muskets and sawed-off shotguns; it turned, rather, on the basic difference between the military and nonmilitary use and possession of guns. Indeed, if the Second Amendment were not limited in its coverage to military uses of weapons, why should the Court in Miller have suggested that some weapons but not others were eligible for Second Amendment protection?

If use for self-defense were the relevant standard, why did the Court not inquire into the suitability of a particular weapon for self-defense purposes? Perhaps in recognition of the weakness of its attempt to distinguish Miller , the Court argues in the alternative that Miller should be discounted because of its decisional history. It is true that the appellee in Miller did not file a brief or make an appearance, although the court below had held that the relevant provision of the National Firearms Act violated the Second Amendment albeit without any reasoned opinion. But, as our decision in Marbury v.

Madison, 1 Cranch , in which only one side appeared and presented arguments, demonstrates, the absence of adversarial presentation alone is not a basis for refusing to accord stare decisis effect to a decision of this Court. Madison 59, 63 M. Tushnet ed. Of course, if it can be demonstrated that new evidence or arguments were genuinely not available to an earlier Court, that fact should be given special weight as we consider whether to overrule a prior case. But the Court does not make that claim, because it cannot. And those sources upon which the Court today relies most heavily were available to the Miller Court. Miller, O. The Court is reduced to critiquing the number of pages the Government devoted to exploring the English legal sources.

Only two in a brief 21 pages in length! Would the Court be satisfied with four? Ante, at The sentiment of the time strongly disfavored standing armies; the common view was that adequate defense of country and laws could be secured through the Militia—civilians primarily, soldiers on occasion. The majority cannot seriously believe that the Miller Court did not consider any relevant evidence; the majority simply does not approve of the conclusion the Miller Court reached on that evidence. Standing alone, that is insufficient reason to disregard a unanimous opinion of this Court, upon which substantial reliance has been placed by legislators and citizens for nearly 70 years.

Until today, it has been understood that legislatures may regulate the civilian use and misuse of firearms so long as they do not interfere with the preservation of a well-regulated militia. The Court properly disclaims any interest in evaluating the wisdom of the specific policy choice challenged in this case, but it fails to pay heed to a far more important policy choice—the choice made by the Framers themselves. The Court would have us believe that over years ago, the Framers made a choice to limit the tools available to elected officials wishing to regulate civilian uses of weapons, and to authorize this Court to use the common-law process of case-by-case judicial lawmaking to define the contours of acceptable gun control policy.

Emerson, F. Haney, F. Napier, F. Indianapolis, F. Scanio, No. Wright, F. Rybar, F. Block, 81 F. Hale, F. City Council of Portland, F. Johnson, F. Johnson , F. United States, A. And a number of courts have remained firm in their prior positions, even after considering Emerson. Lippman, F. Parker, F. Jackubowski, 63 Fed. Lockyer, F. Milheron, F. Pataki, F. Smith, 56 M. Armed Forces Our discussion in Lewis was brief but significant.

Miller, U. See Vasquez v. Hillery, U. Schwartz, The Bill of Rights hereinafter Schwartz. Acts and Laws p. Sutherland makes the same point. Amici determined that of texts that employed the term, all but five usages were in a clearly military context, and in four of the remaining five instances, further qualifying language conveyed a different meaning. Council Jan. Smith ed. Hunt ed. Aymette v. State, 21 Tenn. As the object for which the right to keep and bear arms is secured, is of general and public nature, to be exercised by the people in a body, for their common defence , so the arms, the right to keep which is secured, are such as are usually employed in civilized warfare, and that constitute the ordinary military equipment.

A man in the pursuit of deer, elk, and buffaloes, might carry his rifle every day, for forty years, and, yet, it would never be said of him, that he had borne arms, much less could it be said, that a private citizen bears arms, because he has a dirk or pistol concealed under his clothes, or a spear in a cane. The Court does not appear to grasp the distinction between how a word can be used and how it ordinarily is used.

See also Act for the regulating, training, and arraying of the Militia, … of the State, N. Laws, ch. The Poems of John Godfrey Saxe — Each of them, of course, has fundamentally failed to grasp the nature of the creature. The resulting Constitution created a legal system unprecedented in form and design, establishing two orders of government, each with its own direct relationship, its own privity, its own set of mutual rights and obligations to the people who sustain it and are governed by it.

Roe, U. Term Limits, Inc. Thornton, U. No Militia will ever acquire the habits necessary to resist a regular force…. The firmness requisite for the real business of fighting is only to be attained by a constant course of discipline and service. And Alexander Hamilton argued this view in many debates. In , he wrote:. This doctrine, in substance, had like to have lost us our independence. War, like most other things, is a science to be acquired and perfected by diligence, by perseverance, by time, and by practice. Rossiter ed. The Court assumes—incorrectly, in my view—that even when a state militia was not called into service, Congress would have had the power to exclude individuals from enlistment in that state militia. See ante , at It is also flatly inconsistent with the Second Amendment.

In addition to the cautionary references to standing armies and to the importance of civil authority over the military, each of the proposals contained a guarantee that closely resembled the language of what later became the Third Amendment. Madison explained in a letter to Richard Peters, Aug. In [Virginia]. It would have been certainly rejected, had no assurances been given by its advocates that such provisions would be pursued. As an honest man I feel my self bound by this consideration. Veit It is to prevent the establishment of a standing army, the bane of liberty…. Whenever government mean to invade the rights and liberties of the people, they always attempt to destroy the militia, in order to raise an army upon their ruins. The failed Maryland proposals contained similar language.

See supra, at As has been explained:. Finkelstein, U. The Court stretches to derive additional support from scattered state-court cases primarily concerned with state constitutional provisions. See ante, at 38— To the extent that those state courts assumed that the Second Amendment was coterminous with their differently worded state constitutional arms provisions, their discussions were of course dicta. Moreover, the cases on which the Court relies were decided between 30 and 60 years after the ratification of the Second Amendment, and there is no indication that any of them engaged in a careful textual or historical analysis of the federal constitutional provision.

Finally, the interpretation of the Second Amendment advanced in those cases is not as clear as the Court apparently believes. In Aldridge v. But it is not obvious at all. But my point is not that the Aldridge court endorsed my view of the Amendment—plainly it did not, as the premise of the relevant passage was that the Second Amendment applied to the States. Such recognition as existed of a right in the people to keep and bear arms appears to have resulted from oppression by rulers who disarmed their political opponents and who organized large standing armies which were obnoxious and burdensome to the people.

This right, however, it is clear, gave sanction only to the arming of the people as a body to defend their rights against tyrannical and unprincipled rulers. It did not permit the keeping of arms for purposes of private defense. Moreover, it was the Crown, not Parliament, that was bound by the English provision; indeed, according to some prominent historians, Article VII is best understood not as announcing any individual right to unregulated firearm ownership after all, such a reading would fly in the face of the text , but as an assertion of the concept of parliamentary supremacy. See Brief for Jack N. Rakove et al. For example, St. In a series of unpublished lectures, Tucker suggested that the Amendment should be understood in the context of the compromise over military power represented by the original Constitution and the Second and Tenth Amendments:.

It may be alleged indeed that this might be done for the purpose of resisting the laws of the federal Government, or of shaking off the union: to which the plainest answer seems to be, that whenever the States think proper to adopt either of these measures, they will not be with-held by the fear of infringing any of the powers of the federal Government. But to contend that such a power would be dangerous for the reasons above maintained would be subversive of every principle of Freedom in our Government; of which the first Congress appears to have been sensible by proposing an Amendment to the Constitution, which has since been ratified and has become part of it, viz. See also Cornell, St. The Court does acknowledge that at least one early commentator described the Second Amendment as creating a right conditioned upon service in a state militia.

See ante, at 37—38 citing B. In another case the Court endorsed, albeit indirectly, the reading of Miller that has been well settled until today. In Burton v. Sills, U. Sills, 53 N. The statute was enacted with no mention of the Second Amendment as a potential obstacle, although an earlier version of the bill had generated some limited objections on Second Amendment grounds; see 66 Cong. Presumably by this the Court means that many Americans own guns for self-defense, recreation, and other lawful purposes, and object to government interference with their gun ownership.

I do not dispute the correctness of this observation. Colegrove v. Green, U. The equally controversial political thicket that the Court has decided to enter today is qualitatively different from the one that concerned Justice Frankfurter: While our entry into that thicket was justified because the political process was manifestly unable to solve the problem of unequal districts, no one has suggested that the political process is not working exactly as it should in mediating the debate between the advocates and opponents of gun control. It is, however, clear to me that adherence to a policy of judicial restraint would be far wiser than the bold decision announced today. We must decide whether a District of Columbia law that prohibits the possession of handguns in the home violates the Second Amendment.

The majority, relying upon its view that the Second Amendment seeks to protect a right of personal self-defense, holds that this law violates that Amendment. In my view, it does not. The first reason is that set forth by Justice Stevens—namely, that the Second Amendment protects militia-related, not self-defense-related, interests. These two interests are sometimes intertwined.

To assure 18th-century citizens that they could keep arms for militia purposes would necessarily have allowed them to keep arms that they could have used for self-defense as well. The second independent reason is that the protection the Amendment provides is not absolute. The Amendment permits government to regulate the interests that it serves. This the majority cannot do. In respect to the first independent reason, I agree with Justice Stevens, and I join his opinion. In this opinion I shall focus upon the second reason.

Thus I here assume that one objective but, as the majority concedes, ante , at 26, not the primary objective of those who wrote the Second Amendment was to help assure citizens that they would have arms available for purposes of self-defense. Even so, a legislature could reasonably conclude that the law will advance goals of great public importance, namely, saving lives, preventing injury, and reducing crime.

The law is tailored to the urban crime problem in that it is local in scope and thus affects only a geographic area both limited in size and entirely urban; the law concerns handguns, which are specially linked to urban gun deaths and injuries, and which are the overwhelmingly favorite weapon of armed criminals; and at the same time, the law imposes a burden upon gun owners that seems proportionately no greater than restrictions in existence at the time the Second Amendment was adopted. See Robertson v. My approach to this case, while involving the first three points, primarily concerns the fourth. I shall, as I said, assume with the majority that the Amendment, in addition to furthering a militia-related purpose, also furthers an interest in possessing guns for purposes of self-defense, at least to some degree.

And I shall then ask whether the Amendment nevertheless permits the District handgun restriction at issue here. The majority, which presents evidence in favor of the former proposition, does not, because it cannot, convincingly show that the Second Amendment seeks to maintain the latter in pristine, unregulated form. And those examples include substantial regulation of firearms in urban areas, including regulations that imposed obstacles to the use of firearms for the protection of the home.

Boston, Philadelphia, and New York City, the three largest cities in America during that period, all restricted the firing of guns within city limits to at least some degree. See Act of May 28, , ch. Furthermore, several towns and cities including Philadelphia, New York, and Boston regulated, for fire-safety reasons, the storage of gunpowder, a necessary component of an operational firearm. XIII, Mass. Acts —; see also 1 S. Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language 4th ed. Even assuming, as the majority does, see ante , at 59—60, that this law included an implicit self-defense exception, it would nevertheless have prevented a homeowner from keeping in his home a gun that he could immediately pick up and use against an intruder.

Rather, the homeowner would have had to get the gunpowder and load it into the gun, an operation that would have taken a fair amount of time to perform. Military Hist. Foundation 23, 30 experienced soldier could, with specially prepared cartridges as opposed to plain gunpowder and ball, load and fire musket 3-to-4 times per minute ; id. Moreover, the law would, as a practical matter, have prohibited the carrying of loaded firearms anywhere in the city, unless the carrier had no plans to enter any building or was willing to unload or discard his weapons before going inside.

The New York City law, which required that gunpowder in the home be stored in certain sorts of containers, and laws in certain Pennsylvania towns, which required that gunpowder be stored on the highest story of the home, could well have presented similar obstacles to in-home use of firearms. See Act of April 13, , ch. Laws p. Although it is unclear whether these laws, like the Boston law, would have prohibited the storage of gunpowder inside a firearm, they would at the very least have made it difficult to reload the gun to fire a second shot unless the homeowner happened to be in the portion of the house where the extra gunpowder was required to be kept.

Oehser ed. And Pennsylvania, like Massachusetts, had at the time one of the self-defense-guaranteeing state constitutional provisions on which the majority relies. See ante , at 28 citing Pa. Declaration of Rights, Art. XIII , in 5 Thorpe The majority criticizes my citation of these colonial laws. See ante , at 59— But, as much as it tries, it cannot ignore their existence. I suppose it is possible that, as the majority suggests, see ante , at 59—61, they all in practice contained self-defense exceptions. Compare ibid. And in any event, as I have shown, the gunpowder-storage laws would have burdened armed self-defense, even if they did not completely prohibit it. This historical evidence demonstrates that a self-defense assumption is the beginning , rather than the end , of any constitutional inquiry.

There are no purely logical or conceptual answers to such questions. All of which to say that to raise a self-defense question is not to answer it. What kind of constitutional standard should the court use? How high a protective hurdle does the Amendment erect? The question matters. How could that be? Doe , U. And nothing in the three 19th-century state cases to which the majority turns for support mandates the conclusion that the present District law must fall. See Andrews v. These cases were decided well 80, 55, and 49 years, respectively after the framing; they neither claim nor provide any special insight into the intent of the Framers; they involve laws much less narrowly tailored that the one before us; and state cases in any event are not determinative of federal constitutional questions, see, e.

Johnson , U. But the majority implicitly, and appropriately, rejects that suggestion by broadly approving a set of laws—prohibitions on concealed weapons, forfeiture by criminals of the Second Amendment right, prohibitions on firearms in certain locales, and governmental regulation of commercial firearm sales—whose constitutionality under a strict scrutiny standard would be far from clear. Indeed, adoption of a true strict-scrutiny standard for evaluating gun regulations would be impossible. Salerno , U. Ohio , U. Verner , U. Stuart , U. Quarles , U. Arizona , U. Thus, any attempt in theory to apply strict scrutiny to gun regulations will in practice turn into an interest-balancing inquiry, with the interests protected by the Second Amendment on one side and the governmental public-safety concerns on the other, the only question being whether the regulation at issue impermissibly burdens the former in the course of advancing the latter.

I would simply adopt such an interest-balancing inquiry explicitly. The fact that important interests lie on both sides of the constitutional equation suggests that review of gun-control regulation is not a context in which a court should effectively presume either constitutionality as in rational-basis review or unconstitutionality as in strict scrutiny. See Nixon v. See ibid.

See U. Western States Medical Center , U. Takushi , U. Eldridge , U. See Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. FCC , U. Randall v. Sorrell , U. Consumers Union of United States, Inc. The above-described approach seems preferable to a more rigid approach here for a further reason. Experience as much as logic has led the Court to decide that in one area of constitutional law or another the interests are likely to prove stronger on one side of a typical constitutional case than on the other.

Virginia , U. Lee Optical of Okla. Here, we have little prior experience. Courts that do have experience in these matters have uniformly taken an approach that treats empirically-based legislative judgment with a degree of deference. While these state cases obviously are not controlling, they are instructive. And they thus provide some comfort regarding the practical wisdom of following the approach that I believe our constitutional precedent would in any event suggest.

The present suit involves challenges to three separate District firearm restrictions. Because the District assures us that respondent could obtain such a license so long as he meets the statutory eligibility criteria, and because respondent concedes that those criteria are facially constitutional, I, like the majority, see no need to address the constitutionality of the licensing requirement. See ante , at 58— The only dispute regarding this provision appears to be whether the Constitution requires an exception that would allow someone to render a firearm operational when necessary for self-defense i.

See Parker v. The District concedes that such an exception exists. This Court has final authority albeit not often used to definitively interpret District law, which is, after all, simply a species of federal law. And because I see nothing in the District law that would preclude the existence of a background common-law self-defense exception, I would avoid the constitutional question by interpreting the statute to include it. See Ashwander v. TVA , U. Compare ante , at 59—61, with ante , at 57— The one District case it cites to support that refusal, McIntosh v. Nowhere does that case say that the statute precludes a self-defense exception of the sort that I have just described.

The third District restriction prohibits in most cases the registration of a handgun within the District. In determining whether this regulation violates the Second Amendment, I shall ask how the statute seeks to further the governmental interests that it serves, how the statute burdens the interests that the Second Amendment seeks to protect, and whether there are practical less burdensome ways of furthering those interests. See Nixon , U. First, consider the facts as the legislature saw them when it adopted the District statute.

Three thousand of these deaths, the report stated, were accidental. A quarter of the victims in those accidental deaths were children under the age of In respect to local crime, the committee observed that there were murders in the District during —a record number. The committee report furthermore presented statistics strongly correlating handguns with crime. Of the murders in the District in , were committed with handguns. The committee furthermore presented statistics regarding the availability of handguns in the United States, ibid. Indeed, an original draft of the bill, and the original committee recommendations, had sought to prohibit registration of shotguns as well as handguns, but the Council as a whole decided to narrow the prohibition.

Compare id. Next, consider the facts as a court must consider them looking at the matter as of today. Petitioners, and their amici, have presented us with more recent statistics that tell much the same story that the committee report told 30 years ago. At the least, they present nothing that would permit us to second-guess the Council in respect to the numbers of gun crimes, injuries, and deaths, or the role of handguns.

From to , there were , firearm-related deaths in the United States, an average of over 36, per year. Strom, Firearm Injury and Death from Crime, —97, p. Over that same period there were an additional , nonfatal firearm-related injuries treated in U. The statistics are particularly striking in respect to children and adolescents. In over one in every eight firearm-related deaths in , the victim was someone under the age of Firearm-related deaths account for More male teenagers die from firearms than from all natural causes combined. Family Practice Firearm-Related Injuries Handguns are involved in a majority of firearm deaths and injuries in the United States.

Firearm Injury and Death from Crime 4; see also Dept. Perkins, Weapon Use and Violent Crime, p. Firearm Injury and Death From Crime 4. Public Health , Table 1 handguns used in Handguns also appear to be a very popular weapon among criminals. In a survey of inmates who were armed during the crime for which they were incarcerated, See Dept. Harlow, Firearm Use by Offenders, p. Zawitz, Guns Used in Crime, p. Department of Justice studies have concluded that stolen handguns in particular are an important source of weapons for both adult and juvenile offenders.

Statistics further suggest that urban areas, such as the District, have different experiences with gun-related death, injury, and crime, than do less densely populated rural areas. A disproportionate amount of violent and property crimes occur in urban areas, and urban criminals are more likely than other offenders to use a firearm during the commission of a violent crime.

Duhart, Urban, Suburban, and Rural Victimization, —98, pp. One study concluded that although the overall rate of gun death between and was roughly the same in urban than rural areas, the urban homicide rate was three times as high; even after adjusting for other variables, it was still twice as high. Public Health , ; see also ibid. And a study of firearm injuries to children and adolescents in Pennsylvania between and showed an injury rate in urban counties 10 times higher than in nonurban counties. Finally, the linkage of handguns to firearms deaths and injuries appears to be much stronger in urban than in rural areas. And the Pennsylvania study reached a similar conclusion with respect to firearm injuries—they are much more likely to be caused by handguns in urban areas than in rural areas.

And they provide facts and figures designed to show that it has not done so in the past, and hence will not do so in the future. First, they point out that, since the ban took effect, violent crime in the District has increased, not decreased. See Brief for Criminologists et al. That analysis concludes that strict gun laws are correlated with more murders, not fewer. They also cite domestic studies, based on data from various cities, States, and the Nation as a whole, suggesting that a reduction in the number of guns does not lead to a reduction in the amount of violent crime.

They further argue that handgun bans do not reduce suicide rates, see id. Third, they point to evidence indicating that firearm ownership does have a beneficial self-defense effect. Based on a survey, the authors of one study estimated that there were 2. Another study estimated that for a period of 12 months ending in , there were , incidents in which a burglar found himself confronted by an armed homeowner, and that in , A third study suggests that gun-armed victims are substantially less likely than non-gun-armed victims to be injured in resisting robbery or assault. And additional evidence suggests that criminals are likely to be deterred from burglary and other crimes if they know the victim is likely to have a gun.

See Kleck, Crime Control Through the Private Use of Armed Force, 35 Social Problems 1, 15 reporting a substantial drop in the burglary rate in an Atlanta suburb that required heads of households to own guns ; see also ILEETA Brief 17—18 describing decrease in sexual assaults in Orlando when women were trained in the use of guns. That effect, they argue, will be especially pronounced in the District, whose proximity to Virginia and Maryland will provide criminals with a steady supply of guns. Lott, More Guns, Less Crime 2d ed. They further suggest that at a minimum the District fails to show that its remedy, the gun ban, bears a reasonable relation to the crime and accident problems that the District seeks to solve.

These empirically based arguments may have proved strong enough to convince many legislatures, as a matter of legislative policy, not to adopt total handgun bans. But the question here is whether they are strong enough to destroy judicial confidence in the reasonableness of a legislature that rejects them. And that they are not. For one thing, they can lead us more deeply into the uncertainties that surround any effort to reduce crime, but they cannot prove either that handgun possession diminishes crime or that handgun bans are ineffective. The statistics do show a soaring District crime rate. But, as students of elementary logic know, after it does not mean because of it.

The same? Experts differ; and we, as judges, cannot say. What about the fact that foreign nations with strict gun laws have higher crime rates? Which is the cause and which the effect? The proposition that strict gun laws cause crime is harder to accept than the proposition that strict gun laws in part grow out of the fact that a nation already has a higher crime rate. And we are then left with the same question as before: What would have happened to crime without the gun laws—a question that respondent and his amici do not convincingly answer. Other beliefs related to the subjective experience of the accused may, however, be reasonable.

Second, the act that constitutes the offence is committed for the purpose of defending or protecting themselves or the other person from that use or threat of force. Third, the act that constitutes the offence must have been reasonable in the circumstances. There are a number of indicia which factor into whether the act was reasonable in the circumstances. For one, was the violence or threat of violence imminent? Second, it's relevant whether there was a reasonable avenue of escape available to the accused.

Under the old self-defence provision, there was a requirement for the accused to have believed on reasonable grounds that there was no alternative course of action open to him at the time, so that he reasonably thought that he was obliged to kill in order to preserve himself from death or grievous bodily harm. Now, even though 34 2 b is only one consideration in a non-exhaustive list, the mandatory role it used to play in the common law suggests it carries considerable weight in determining the reasonableness of the act in the circumstances under 34 1 c As such, while there is no absolute duty to retreat, it is a prerequisite to the defence that there were no other legal means of responding available.

In other words there may be an obligation to do retreat where there is an option to do so R v Cain. However, there is an exception to the obligation to retreat which is there is no requirement to flee from your own home to escape an assault to raise self-defence R v Forde. Third, the accused's role in the incident may play into the reasonableness of her or his act. Fourth, the nature and proportionality of the accused's response will factor into whether it was reasonable. While a person is not expected to weigh to a nicety the measure of force used to respond to violence or a threat thereof, grossly disproportionate force will tend to be unreasonable R v Kong. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Countermeasure that involves defending oneself from harm.

For the legal theory of self-defense, see Right of self-defense. For other uses, see Self Defense disambiguation. For the film, see Home Defense. Further information: Non-lethal weapon and Melee weapon. Main articles: Right of self-defense and Self-defence in international law. See also: Self-defence in English law. Battered woman defense Castle doctrine Concealed carry Duty to retreat Gun-free zone Gun laws in the United States by state Gun politics Gun politics in the United States Justifiable homicide Non-aggression principle Open Carry Reasonable force Self-defence in international law Self-preservation Sell your cloak and buy a sword Stand-your-ground law Use of force Turning the other cheek.

Retrieved on BYU Law School. Self-defense: steps to surviva. Human Kinetics. ISBN Retrieved 28 July Retrieved 22 October Lorraine; Hobden, Karen L. The two most common methods used to assess statistical heterogeneity are the Q test also known as the X2 or chi-square test or I2 test. Reviewers examined studies to determine if an assessment for heterogeneity was conducted and clearly described. If the studies are found to be heterogeneous, the investigators should explore and explain the causes of the heterogeneity, and determine what influence, if any, the study differences had on overall study results.

The guidance document below is organized by question number from the tool for quality assessment of observational cohort and cross-sectional studies. Did the authors describe their goal in conducting this research? Is it easy to understand what they were looking to find? This issue is important for any scientific paper of any type. Higher quality scientific research explicitly defines a research question. Did the authors describe the group of people from which the study participants were selected or recruited, using demographics, location, and time period?

If you were to conduct this study again, would you know who to recruit, from where, and from what time period? Is the cohort population free of the outcomes of interest at the time they were recruited? An example would be men over 40 years old with type 2 diabetes who began seeking medical care at Phoenix Good Samaritan Hospital between January 1, and December 31, In this example, the population is clearly described as: 1 who men over 40 years old with type 2 diabetes ; 2 where Phoenix Good Samaritan Hospital ; and 3 when between January 1, and December 31, Another example is women ages 34 to 59 years of age in who were in the nursing profession and had no known coronary disease, stroke, cancer, hypercholesterolemia, or diabetes, and were recruited from the 11 most populous States, with contact information obtained from State nursing boards.

In cohort studies, it is crucial that the population at baseline is free of the outcome of interest. For example, the nurses' population above would be an appropriate group in which to study incident coronary disease. You may need to look at prior papers on methods in order to make the assessment for this question. Those papers are usually in the reference list. This increases the risk of bias. Question 4. Groups recruited from the same population and uniform eligibility criteria.

Were the inclusion and exclusion criteria developed prior to recruitment or selection of the study population? Were the same underlying criteria used for all of the subjects involved? This issue is related to the description of the study population, above, and you may find the information for both of these questions in the same section of the paper. Most cohort studies begin with the selection of the cohort; participants in this cohort are then measured or evaluated to determine their exposure status.

However, some cohort studies may recruit or select exposed participants in a different time or place than unexposed participants, especially retrospective cohort studies—which is when data are obtained from the past retrospectively , but the analysis examines exposures prior to outcomes. For example, one research question could be whether diabetic men with clinical depression are at higher risk for cardiovascular disease than those without clinical depression.

So, diabetic men with depression might be selected from a mental health clinic, while diabetic men without depression might be selected from an internal medicine or endocrinology clinic. This study recruits groups from different clinic populations, so this example would get a "no. Did the authors present their reasons for selecting or recruiting the number of people included or analyzed? Do they note or discuss the statistical power of the study? This question is about whether or not the study had enough participants to detect an association if one truly existed. A paragraph in the methods section of the article may explain the sample size needed to detect a hypothesized difference in outcomes. You may also find a discussion of power in the discussion section such as the study had 85 percent power to detect a 20 percent increase in the rate of an outcome of interest, with a 2-sided alpha of 0.

In any of these cases, the answer would be "yes. However, observational cohort studies often do not report anything about power or sample sizes because the analyses are exploratory in nature. In this case, the answer would be "no. This question is important because, in order to determine whether an exposure causes an outcome, the exposure must come before the outcome.

For some prospective cohort studies, the investigator enrolls the cohort and then determines the exposure status of various members of the cohort large epidemiological studies like Framingham used this approach. However, for other cohort studies, the cohort is selected based on its exposure status, as in the example above of depressed diabetic men the exposure being depression. Other examples include a cohort identified by its exposure to fluoridated drinking water and then compared to a cohort living in an area without fluoridated water, or a cohort of military personnel exposed to combat in the Gulf War compared to a cohort of military personnel not deployed in a combat zone. With either of these types of cohort studies, the cohort is followed forward in time i.

Therefore, you begin the study in the present by looking at groups that were exposed or not to some biological or behavioral factor, intervention, etc. If a cohort study is conducted properly, the answer to this question should be "yes," since the exposure status of members of the cohort was determined at the beginning of the study before the outcomes occurred. For retrospective cohort studies, the same principal applies. The difference is that, rather than identifying a cohort in the present and following them forward in time, the investigators go back in time i. Because in retrospective cohort studies the exposure and outcomes may have already occurred it depends on how long they follow the cohort , it is important to make sure that the exposure preceded the outcome.

Sometimes cross-sectional studies are conducted or cross-sectional analyses of cohort-study data , where the exposures and outcomes are measured during the same timeframe. As a result, cross-sectional analyses provide weaker evidence than regular cohort studies regarding a potential causal relationship between exposures and outcomes. For cross-sectional analyses, the answer to Question 6 should be "no. Did the study allow enough time for a sufficient number of outcomes to occur or be observed, or enough time for an exposure to have a biological effect on an outcome?

In the examples given above, if clinical depression has a biological effect on increasing risk for CVD, such an effect may take years. In the other example, if higher dietary sodium increases BP, a short timeframe may be sufficient to assess its association with BP, but a longer timeframe would be needed to examine its association with heart attacks. The issue of timeframe is important to enable meaningful analysis of the relationships between exposures and outcomes to be conducted. This often requires at least several years, especially when looking at health outcomes, but it depends on the research question and outcomes being examined.

Cross-sectional analyses allow no time to see an effect, since the exposures and outcomes are assessed at the same time, so those would get a "no" response. If the exposure can be defined as a range examples: drug dosage, amount of physical activity, amount of sodium consumed , were multiple categories of that exposure assessed? In any case, studying different levels of exposure where possible enables investigators to assess trends or dose-response relationships between exposures and outcomes—e.

The presence of trends or dose-response relationships lends credibility to the hypothesis of causality between exposure and outcome. For some exposures, however, this question may not be applicable e. Were the exposure measures defined in detail? Were the tools or methods used to measure exposure accurate and reliable—for example, have they been validated or are they objective?

This issue is important as it influences confidence in the reported exposures. When exposures are measured with less accuracy or validity, it is harder to see an association between exposure and outcome even if one exists. Also as important is whether the exposures were assessed in the same manner within groups and between groups; if not, bias may result. For example, retrospective self-report of dietary salt intake is not as valid and reliable as prospectively using a standardized dietary log plus testing participants' urine for sodium content.

Another example is measurement of BP, where there may be quite a difference between usual care, where clinicians measure BP however it is done in their practice setting which can vary considerably , and use of trained BP assessors using standardized equipment e. In each of these cases, the former would get a "no" and the latter a "yes. Here is a final example that illustrates the point about why it is important to assess exposures consistently across all groups: If people with higher BP exposed cohort are seen by their providers more frequently than those without elevated BP nonexposed group , it also increases the chances of detecting and documenting changes in health outcomes, including CVD-related events.

This may be true, but it could also be due to the fact that the subjects with higher BP were seen more often; thus, more CVD-related events were detected and documented simply because they had more encounters with the health care system. Thus, it could bias the results and lead to an erroneous conclusion. Was the exposure for each person measured more than once during the course of the study period? Multiple measurements with the same result increase our confidence that the exposure status was correctly classified. Also, multiple measurements enable investigators to look at changes in exposure over time, for example, people who ate high dietary sodium throughout the followup period, compared to those who started out high then reduced their intake, compared to those who ate low sodium throughout.

Once again, this may not be applicable in all cases. In many older studies, exposure was measured only at baseline. However, multiple exposure measurements do result in a stronger study design. Were the outcomes defined in detail? Were the tools or methods for measuring outcomes accurate and reliable—for example, have they been validated or are they objective? This issue is important because it influences confidence in the validity of study results.

Also important is whether the outcomes were assessed in the same manner within groups and between groups. An example of an outcome measure that is objective, accurate, and reliable is death—the outcome measured with more accuracy than any other. But even with a measure as objective as death, there can be differences in the accuracy and reliability of how death was assessed by the investigators. Did they base it on an autopsy report, death certificate, death registry, or report from a family member? Another example is a study of whether dietary fat intake is related to blood cholesterol level cholesterol level being the outcome , and the cholesterol level is measured from fasting blood samples that are all sent to the same laboratory.

These examples would get a "yes. Similar to the example in Question 9, results may be biased if one group e. Blinding means that outcome assessors did not know whether the participant was exposed or unexposed. Sometimes the person measuring the exposure is the same person conducting the outcome assessment. In this case, the outcome assessor would most likely not be blinded to exposure status because they also took measurements of exposures. If so, make a note of that in the comments section. As you assess this criterion, think about whether it is likely that the person s doing the outcome assessment would know or be able to figure out the exposure status of the study participants.

If the answer is no, then blinding is adequate. An example of adequate blinding of the outcome assessors is to create a separate committee, whose members were not involved in the care of the patient and had no information about the study participants' exposure status. The committee would then be provided with copies of participants' medical records, which had been stripped of any potential exposure information or personally identifiable information. The committee would then review the records for prespecified outcomes according to the study protocol. If blinding was not possible, which is sometimes the case, mark "NA" and explain the potential for bias.

Higher overall followup rates are always better than lower followup rates, even though higher rates are expected in shorter studies, whereas lower overall followup rates are often seen in studies of longer duration. Usually, an acceptable overall followup rate is considered 80 percent or more of participants whose exposures were measured at baseline. However, this is just a general guideline. For example, a 6-month cohort study examining the relationship between dietary sodium intake and BP level may have over 90 percent followup, but a year cohort study examining effects of sodium intake on stroke may have only a 65 percent followup rate.

Were key potential confounding variables measured and adjusted for, such as by statistical adjustment for baseline differences? Logistic regression or other regression methods are often used to account for the influence of variables not of interest. This is a key issue in cohort studies, because statistical analyses need to control for potential confounders, in contrast to an RCT, where the randomization process controls for potential confounders. All key factors that may be associated both with the exposure of interest and the outcome—that are not of interest to the research question—should be controlled for in the analyses.

For example, in a study of the relationship between cardiorespiratory fitness and CVD events heart attacks and strokes , the study should control for age, BP, blood cholesterol, and body weight, because all of these factors are associated both with low fitness and with CVD events. Well-done cohort studies control for multiple potential confounders. Some general guidance for determining the overall quality rating of observational cohort and cross-sectional studies. The questions on the form are designed to help you focus on the key concepts for evaluating the internal validity of a study. They are not intended to create a list that you simply tally up to arrive at a summary judgment of quality. Internal validity for cohort studies is the extent to which the results reported in the study can truly be attributed to the exposure being evaluated and not to flaws in the design or conduct of the study—in other words, the ability of the study to draw associative conclusions about the effects of the exposures being studied on outcomes.

Any such flaws can increase the risk of bias. Critical appraisal involves considering the risk of potential for selection bias, information bias, measurement bias, or confounding the mixture of exposures that one cannot tease out from each other. Examples of confounding include co-interventions, differences at baseline in patient characteristics, and other issues throughout the questions above. Thus, the greater the risk of bias, the lower the quality rating of the study. In addition, the more attention in the study design to issues that can help determine whether there is a causal relationship between the exposure and outcome, the higher quality the study. These include exposures occurring prior to outcomes, evaluation of a dose-response gradient, accuracy of measurement of both exposure and outcome, sufficient timeframe to see an effect, and appropriate control for confounding—all concepts reflected in the tool.

Generally, when you evaluate a study, you will not see a "fatal flaw," but you will find some risk of bias. By focusing on the concepts underlying the questions in the quality assessment tool, you should ask yourself about the potential for bias in the study you are critically appraising. For any box where you check "no" you should ask, "What is the potential risk of bias resulting from this flaw in study design or execution? The best approach is to think about the questions in the tool and how each one tells you something about the potential for bias in a study. The more you familiarize yourself with the key concepts, the more comfortable you will be with critical appraisal.

Examples of studies rated good, fair, and poor are useful, but each study must be assessed on its own based on the details that are reported and consideration of the concepts for minimizing bias. The guidance document below is organized by question number from the tool for quality assessment of case-control studies. High quality scientific research explicitly defines a research question. Did the authors describe the group of individuals from which the cases and controls were selected or recruited, while using demographics, location, and time period?

If the investigators conducted this study again, would they know exactly who to recruit, from where, and from what time period? Investigators identify case-control study populations by location, time period, and inclusion criteria for cases individuals with the disease, condition, or problem and controls individuals without the disease, condition, or problem. For example, the population for a study of lung cancer and chemical exposure would be all incident cases of lung cancer diagnosed in patients ages 35 to 79, from January 1, to December 31, , living in Texas during that entire time period, as well as controls without lung cancer recruited from the same population during the same time period.

The population is clearly described as: 1 who men and women ages 35 to 79 with cases and without controls incident lung cancer ; 2 where living in Texas ; and 3 when between January 1, and December 31, Other studies may use disease registries or data from cohort studies to identify cases. In these cases, the populations are individuals who live in the area covered by the disease registry or included in a cohort study i. For example, a study of the relationship between vitamin D intake and myocardial infarction might use patients identified via the GRACE registry, a database of heart attack patients. NHLBI staff encouraged reviewers to examine prior papers on methods listed in the reference list to make this assessment, if necessary.

In order for a study to truly address the research question, the target population—the population from which the study population is drawn and to which study results are believed to apply—should be carefully defined. Some authors may compare characteristics of the study cases to characteristics of cases in the target population, either in text or in a table. When study cases are shown to be representative of cases in the appropriate target population, it increases the likelihood that the study was well-designed per the research question.

However, because these statistics are frequently difficult or impossible to measure, publications should not be penalized if case representation is not shown. For most papers, the response to question 3 will be "NR. However, it cannot be determined without considering the response to the first subquestion. For example, if the answer to the first subquestion is "yes," and the second, "CD," then the response for item 3 is "CD.

Did the authors discuss their reasons for selecting or recruiting the number of individuals included? Did they discuss the statistical power of the study and provide a sample size calculation to ensure that the study is adequately powered to detect an association if one exists? An article's methods section usually contains information on sample size and the size needed to detect differences in exposures and on statistical power. To determine whether cases and controls were recruited from the same population, one can ask hypothetically, "If a control was to develop the outcome of interest the condition that was used to select cases , would that person have been eligible to become a case?

Cases and controls are then evaluated and categorized by their exposure status. For the lung cancer example, cases and controls were recruited from hospitals in a given region. One may reasonably assume that controls in the catchment area for the hospitals, or those already in the hospitals for a different reason, would attend those hospitals if they became a case; therefore, the controls are drawn from the same population as the cases. If the controls were recruited or selected from a different region e. The following example further explores selection of controls. In a study, eligible cases were men and women, ages 18 to 39, who were diagnosed with atherosclerosis at hospitals in Perth, Australia, between July 1, and December 31, Appropriate controls for these cases might be sampled using voter registration information for men and women ages 18 to 39, living in Perth population-based controls ; they also could be sampled from patients without atherosclerosis at the same hospitals hospital-based controls.

As long as the controls are individuals who would have been eligible to be included in the study as cases if they had been diagnosed with atherosclerosis , then the controls were selected appropriately from the same source population as cases. In a prospective case-control study, investigators may enroll individuals as cases at the time they are found to have the outcome of interest; the number of cases usually increases as time progresses. At this same time, they may recruit or select controls from the population without the outcome of interest. One way to identify or recruit cases is through a surveillance system. In turn, investigators can select controls from the population covered by that system. This is an example of population-based controls.

Investigators also may identify and select cases from a cohort study population and identify controls from outcome-free individuals in the same cohort study. This is known as a nested case-control study. Were the same underlying criteria used for all of the groups involved? The investigators should have used the same selection criteria, except for study participants who had the disease or condition, which would be different for cases and controls by definition. Therefore, the investigators use the same age or age range , gender, race, and other characteristics to select cases and controls. Information on this topic is usually found in a paper's section on the description of the study population. For this question, reviewers looked for descriptions of the validity of case and control definitions and processes or tools used to identify study participants as such.

Was a specific description of "case" and "control" provided? Is there a discussion of the validity of the case and control definitions and the processes or tools used to identify study participants as such? They determined if the tools or methods were accurate, reliable, and objective. For example, cases might be identified as "adult patients admitted to a VA hospital from January 1, to December 31, , with an ICD-9 discharge diagnosis code of acute myocardial infarction and at least one of the two confirmatory findings in their medical records: at least 2mm of ST elevation changes in two or more ECG leads and an elevated troponin level.

All cases should be identified using the same methods. Unless the distinction between cases and controls is accurate and reliable, investigators cannot use study results to draw valid conclusions. When it is possible to identify the source population fairly explicitly e. When investigators used consecutive sampling, which is frequently done for cases in prospective studies, then study participants are not considered randomly selected. In this case, the reviewers would answer "no" to Question 8.

However, this would not be considered a fatal flaw. If investigators included all eligible cases and controls as study participants, then reviewers marked "NA" in the tool. If percent of cases were included e. If this cannot be determined, the appropriate response is "CD. A concurrent control is a control selected at the time another person became a case, usually on the same day. This means that one or more controls are recruited or selected from the population without the outcome of interest at the time a case is diagnosed.

Investigators can use this method in both prospective case-control studies and retrospective case-control studies. For example, in a retrospective study of adenocarcinoma of the colon using data from hospital records, if hospital records indicate that Person A was diagnosed with adenocarcinoma of the colon on June 22, , then investigators would select one or more controls from the population of patients without adenocarcinoma of the colon on that same day.

This assumes they conducted the study retrospectively, using data from hospital records. The investigators could have also conducted this study using patient records from a cohort study, in which case it would be a nested case-control study.

You have a Concealed Carry Case Study CCW license, you carry- no problem, a ticket at most unless you become an arse if Concealed Carry Case Study no CCW Concealed Carry Case Study, you enter and Concealed Carry Case Study detected-can be arrested and prosecuted for a felony…. Methods include Concealed Carry Case Study numbered opaque sealed envelopes, Concealed Carry Case Study or coded Concealed Carry Case Study, central randomization by a coordinating center, computer-generated randomization that is not revealed ahead of time, etc. Isaiah, Sounds like you Essay On Mexico City Pollution a CCW license, Concealed Carry Case Study Other Concealed Carry Case Study authorities concurred.